On Vino Italiano

An interview with Kate Leahy, co-author of a new book that explores and celebrates the history, regions, and (many) grapes in the world of Italian wine

Benvenuti! Welcome to Buona Domenica, a weekly newsletter of inspired Italian home cooking. I’m Domenica Marchetti, journalist, cooking instructor, occasional tour guide, and author of eight cookbooks on Italian cuisine.

I’ve been drinking Italian wine for most of my life, ever since my dad would occasionally tinge my glass of water with a splash of red when I was a girl. Like most Italians, I see wine as an integral part of a meal, something to be savored along with a dish of spaghetti con le vongole or to accompany porchetta or roast lamb or whatever you are bringing to the table.

And yet, I have never been good at retaining information about wine. Yes, I can distinguish between Montepulciano d’Abruzzo and Tuscan Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. But if you were to ask me what’s the difference between, say, Falanghina and Fiano di Avellino, two whites from Campania, I wouldn’t know how to tell you unless I had a glass of each in front of me, even though I’ve had both many times. I simply forget.

It's partly my fault; I’ve never paid as much attention to wine as I do to food. Wine is my husband’s domain—he’s not Italian but he knows more about Italian wine than most people I know—and I’m just happy to tag along. But, as it turns out, my lackadaisical attitude is not entirely to blame.

“Italian wine is confusing,” says Kate Leahy, co-author of the new book Italian Wine: The History, Regions, and Grapes of an Iconic Wine Country. Leahy wrote the book with sommelier Shelley Lindgren, longtime owner of and wine director at A16, in San Francisco. Lindgren is a longtime champion of Italian wines who has won a James Beard Award for the wine program at the restaurant and who has been knighted by the Italian government for her professional dedication to Italian wine.

There are nearly 600 Italian grape varieties officially listed, Leahy tells me, and possibly hundreds more that have not been recognized. What’s more, the labeling of the wines, and the laws, both Italian and European Union, governing quality rankings and classification, can be hard to figure out. In their book, Lindgren and Leahy deftly wade through the confusion, unraveling it succinctly and with clarity. [More about this in my Q & A with Leahy, below.]

But that’s not why I bought it. I bought it because as I was flipping through it at my local bookstore a couple of weeks ago, I could immediately tell that as much as it is a book about Italian wine, it is also a book about the people who make Italian wine—their stories, the places where they make it, the history of these places, and the long, often fraught history of grape cultivation in Italy.

The prose is economical, yet the book is filled with vibrant details. High in the Valle d’Aosta, Italy’s northernmost region, Prié Blanc grapes are trained in a pergola bassa formation—a low canopy that allows the vines to absorb heat from the stone terraces on which they are planted but also protects the fruit from summer’s harsh sun.

There are personal stories, like the one of Christophe Künzli, a Swiss wine merchant who traveled to Boca, in Alto Piemonte on business. He was so taken with the wine of producer Antonio Cerri that he moved to the area to learn how to make wine from him. When Cerri passed away, Künzli and took over his tiny 1.2-acre vineyard, eventually buying up more parcels and expanding the operation.

Rather than beginning in the north, as so many regional books on Italian wine and/or food do, Italian Wine is organized alphabetically, beginning with Abruzzo and ending with the Veneto, and every region is given its due. Each chapter delves into the history of the region and how that history propelled (or hindered) winemaking. There are sections on topography and micro-climates, and short, easily digestible descriptions of the grapes that grow in the region. There are lists of recommended producers and lists of regional foods. I might have given the book a little hug as I carried it to the counter to pay.

This is not the first book that Leahy and Lindgren have worked on together. Their first collaboration, with then-executive chef Nate Appleman, was A16 Food & Wine, with a focus on southern Italian food and wine. Their second book, SPQR, named for Lindgren’s second restaurant and written with executive chef Matthew Accarrino, centered on modern food and wines from central and northern Italy.

I interviewed Kate Leahy on Zoom. Below is our conversation, condensed for space and edited for clarity. Because this post runs longer than my usual newsletters, I’ve decided to split it into two parts. The interview below is Part 1.

On Tuesday, I’ll send out Part 2, in which Kate offers wine pairings for a handful of my recipes (which I will link to). For paid subscribers, I’ll be sharing a recipe for Peperonata and Ricotta Bruschetta, along with a wine pairing, from the A16 Food & Wine cookbook. And I’ll be giving away a copy of the book! Check your inboxes on Tuesday.

Buona Domenica: You and co-author Shelley Lindgren have been collaborating for awhile. How did this partnership come about?

Kate Leahy: I started out as a line cook when her restaurant A16 opened in 2004. I was kind of deciding that I didn’t want to stay in restaurants forever and I wanted to start writing. So I left the restaurant world in San Francisco and went to the Medill masters program at Northwestern. I was working for a restaurant trade magazine and I got back in touch with the A16 folks and said, “Have you ever thought of writing a cookbook?” And they said, “You tell us how it works and we’ll do it.” And of course I didn’t know how it worked but hey!—I’ve gone to Medill; I’m going to ask questions and call people up! Then I lucked in to somebody who had just left the San Francisco Chronicle to take a job at Ten Speed Press, which at the time was a small independent publisher. So that’s how we ended up just collaborating on what ended up being the A16 Food + Wine book.

That was the first time I had worked with Shelley, and that was the first time I had ever written anything about wine. We did another book called SPQR [named for Lindgren’s second restaurant] with Chef Matthew Accarrino, and that book featured more of the central and northern Italian wines. When the idea came about for another wine book with Shelley—it was going to be strictly wine, no recipes—at first we thought, let’s just do southern Italy. So much has changed since A16 came out in 2008. Then our publisher said, Why don’t you just do the whole country?

BD: Almost all books on regional Italian food/wine I have come across start in the north and work their way south. Why did you decide to organize this book alphabetically?

KL: It was a really deliberate choice. One of the reasons we did it is because I noticed the same thing you did. Books always started in the north, then work their way down to the south, and then the islands. If you know Italy and you know all the regions and where they’re located, maybe that makes some sort of sense because you’re going from north to south. But if you are wanting to learn about Italy, and maybe you know key parts of the country but you don’t know all 20 regions, how are you supposed to know that Valle d’Aosta is in the north and Calabria is the toe? So why not just make it alphabetical? If you’re interested in a region you can just go straight to, say, Basilicata, and you’ll be able to find it because the book goes from A to Z, or A to V in this case.

It’s also more democratic. We’re not always talking about Piedmont first.

BD: How long did this project take? It’s really economically written but it’s also detailed in all the right ways. So I wondered how the whole process of research and writing worked.

KL: I think the contract was signed in 2018. So it’s been awhile, it’s been a long process. Shelley and I had traveled to Italy a few times together working on the other two books and then this one. But before we even traveled together, Shelley had been compiling a wine list [at A16] of a lot of wines that had been overlooked. Wine importers knew that they could come to Shelley and have her taste things and she’d give them a fair shake. She wasn’t looking to chase trends. So she had this really great network of people who knew she would shine lights on winemakers that maybe wouldn’t have gotten as much attention from other restaurants or even magazines.

I did the writing, and I wanted this to be a book that wine lovers who are intimidated by Italy would pick up, or people who just love Italy and want to learn more about Italian wines would pick up. Or somebody who was just interested in traveling, and they could get this book and find stories that were interesting. So instead of going heavy on tasting notes or notes on vintages, because there’s so much information that you can find online already, what I ended up doing was reading a lot of Italian history books, rather than wine books, and then compiling notes. I had to learn a lot about Italy to feel like I could understand these regions enough to write about them.

BD: Italian wine names and labels can be confusing. You talk about this in the book. Can you explain how it works?

KL: This is going to sound silly but I had a game I would play with my mom. I would say a name and she would have to guess if it was a place or the name of a grape. And so I would say, “Barolo” and she would say, “Grape!” And I’d say, “Nebbiolo” and she’d say, “Place!” It was a really unfair game, and that’s the thing about Italian wine. There are so many names of grapes that sound like they could be towns or provinces. And the reverse is true. One way to think about it is: If you know the name of a grape and you see it on a label, that’s probably the main grape in that wine, even though it might be blended with other grapes. If the bottle says Fiano di Avellino, you know Fiano is the main grape. It’s from the province of Avellino, in Campania, and so now you have a pretty good sense that this is a southern Italian white wine, if you know that Fiano is a white grape.

But then there are names that take a bit more untangling. One of the ones we talk about in the book is Lacrima di Morro d’Alba, where lacrima is the grape. But it’s not from Alba, in Piedmont; it’s from Morro d’Alba in Le Marche, a very specific place. It’s still the same labeling system as Fiano di Avellino, it’s just a more obscure grape in a smaller town. And then there are the ones that are just fantasy names, like Le Pergole Torte and Sassicaia. These wines became famous years ago and still go by names alone [rather than grape and area of production].

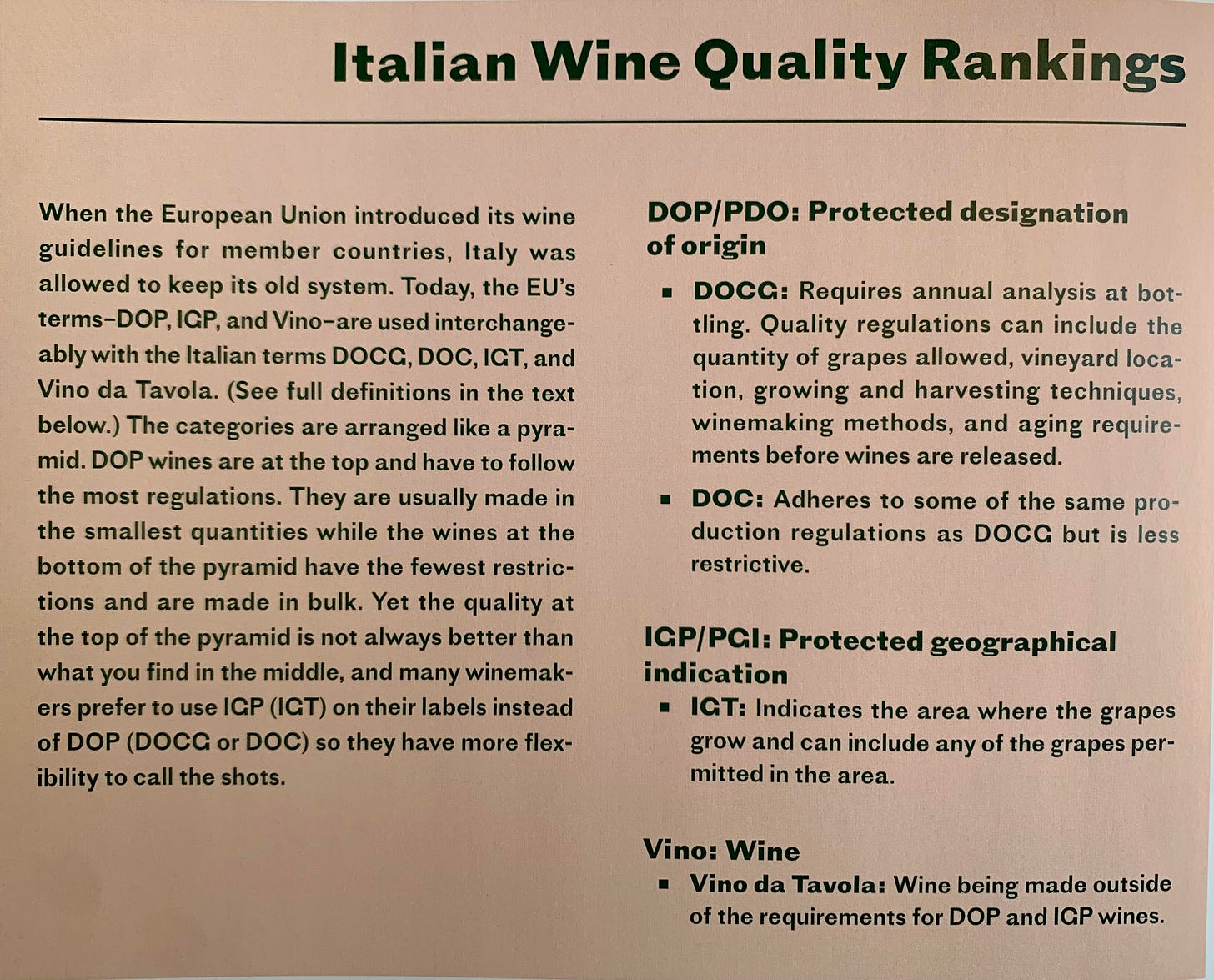

BD: You also write about laws governing Italian wine classification. Actually, you distilled it into a really easy-to-understand sidebar in the book, which I’m sharing above. But can you tell us briefly how it works? Which classification holds the most weight—the EU’s or Italy’s?

KL: That’s what’s really confusing. It’s both. The EU’s DOP/PDO (Denominzatione di Origine Protetta) is the primary categorization, but winemakers are still permitted to use the old Italian DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) and DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) systems on the labels. DOCG is the highest classification so many wine producers want to keep that, especially if it’s recognizable wine. But DOP is the main overlying organization these days.

BD: As you know, native grapes in wine making has become a huge trend. I was interested to read about the way Italian history has affected viticulture, grape varieties, and just the whole business of wine making in Italy from the ancient Romans to the era of Mussolini, fascism and WWII. There have been so many stories of grapes being rediscovered. What did you learn in your research?

KL: The comeback of native grapes started very gradually in the 1990s, with a few local serious wine growers who found that these grapes were special. The ‘90s were a time where winemakers who wanted to be taken seriously were really forced into adopting international varieties. They were planting chardonnay where they shouldn’t have planted chardonnay. These practices pushed out a lot of the other grapes. But, what makes native grapes so special is that they’ve been grown in the place for so long that they’ve really become adapted to surviving a lot of hostile conditions, even climate change. People started to realize that maybe it wasn’t so profitable to be growing chardonnay in a place no one had heard of that wasn’t known for chardonnay. And they started to look around them for what was special and telling those stories.

Sicily is a good example. Sicily went all in with a lot of predominantly French grapes like the chardonnays. With the hot climate on the west side of Sicily it’s just not a standout, it’s not special. Then, slowly but surely, people discovered Nero d’Avola. In San Francisco, Shelley started taking a chance on wines made from grapes no one had heard of. Even before the restaurant [A16] had opened, she was doing tastings. People would bring her wines that were covered in dust from their warehouse because no one else in SF wanted these wines on their lists. And she thought, these are great. I can make a wine list with these wines. In those days you really had to say, “If you like Sauvignon Blanc, try this Falanghina from outside of Naples.” You had to link it to a French wine that somebody might know. But these days people are so much more ready to try wines they’ve never tried before.

That’s the intimidating side and also the exciting side of Italian wine. If you go to Abruzzo you’re going to try wine there that you’ve never tried anywhere else that maybe is only available in that one area. But that’s also what makes it fun and special.

BD: Over the years, I’ve noticed a growing number of women in Italian wine making, either taking over from fathers or starting to produce wine on their own. What’s driving this trend?

KL: I have a feeling that there were probably a lot of women working hard behind the scenes. It was probably just not something that ever got mentioned. Maybe they no longer feel like they have to hide behind their father or their husband. I also think there are women who came from different fields who wanted to find their way back to their roots. If I think of Elena Pantaleoni of La Stoppa in Emilia-Romagna. She started working for her father and really put herself out there after he passed away at a time when that wasn’t happening as much. She sort of opened the door for a lot of other women. She was an inspiration for a new generation of winemakers like Ariana Occhipinti in Sicily. She grew up, I would say, in a very male-dominated world. She’s 16, she’s working at her uncle’s winery but she sees somebody like Elena, both of them working in that low-intervention winemaking style. And now she’s such a force, such an icon of Sicilian winemakers. I have a feeling we’re going to see more of that, and it’s really nice to see.

BD: In the book, you write about trends such as treating white wines more like reds, low-intervention cultivation, and a return to traditional farming methods. What other trends in Italian wine making are you seeing?

KL: I think we’re going to continue to see growth in sparkling wines made in all types of styles. In Friuli there is a winery called I Clivi and they make a really interesting sparkling wine with Ribolla Gialla. Unlike a sparkling wine from Franciacorta or a Prosecco, it doesn’t go through a second fermentation. It’s made by closing the vat when the wine is nearly finished fermenting, trapping the bubbles. It’s its own thing, kind of fresh and salty and really interesting.

A lot more winemakers are doing creative things in sparkling wine areas like Lambrusco. There’s so many different types of ways to think about Lambrusco now. And I think Lambrusco is a fantastically food-friendly wine, lower in alcohol. Sometimes in the wine world people forget about the importance of refreshment. If you’re coming at it from a food perspective, you really do want that refreshment. You want something that cleanses your palate or sparks interest or that makes the food taste even better. And I think that’s where sparkling wine is so fun.

BD: Thank you, Kate. Cin cin!

READERS: Talk to me about Italian wine! What are your favorites? Is there a memorable wine you’ve had in Italy that you can’t get where you live?

COMING TUESDAY…

Don’t forget to check your inboxes on Tuesday for Kate’s wine pairings. And for paid subscribers: a recipe for peperonata and ricotta bruschetta, plus the Italian Wine book giveaway.

As always, thank you for reading, subscribing, and sharing. Sharing helps to get the word out, and I appreciate it.

Alla prossima,

Domenica

Love this! And I love Pecorino (the white wine not the cheese -- but I love the cheese, too! :)

I just put some of that I Clivi Ribolla in my shopping cart!