Catching Up with Karima Moyer-Nocchi

The food historian and author talks about the "deification" of the Italian nonna, the invention of tradition & other prickly subjects; plus, a 17th century recipe for stuffed eggplant

Some months ago, I came across an Instagram account devoted to historical Italian food. It featured photos and recipes for ancient, medieval, and modern Italian dishes. There was a 1684 recipe for confit-style cavolo nero, an 1865 recipe for rice gnocchi in velouté, and a 17th century recipe for herb-stuffed eggplant with sour orange, among others. The recipes were accompanied by historical notes and anecdotes and short video clips.

Hmmm, I thought. I want to know more about the person behind this account. And so a few weeks ago, I found myself chatting on Zoom with Karima Moyer-Nocchi. She is American, by the way, born and raised in Ohio, but has made Italy her home for the past 30+ years. Karima (we go by first names here on Substack) earned a degree in comparative literature at U-Mass Amherst and did post-graduate studies in Florence. Married to an Italian, she is now a professor in the Modern Languages Department at the University of Siena.

Her passion, however, is food history, especially Italian food history. She has a small collection of antique and vintage cookbooks, with a concentration on early 20th century publications, an era in which she is especially interested. But her interest goes far beyond just recipes. She’s written articles taking on misconceptions about classic Italian foods, including this one on pizza. And she has published two books on the subject. The Eternal Table: A Cultural History of Food in Rome (2019) chronicles the evolution of Roman food from the early days of the Empire up to the current global fascination with la cucina romanesca.

Her first book, published in 2015, is Chewing the Fat: An Oral History of Italian Foodways from Fascism to Dolce Vita. It features one-on-one interviews with Italian women in their 90s—women from the north and from the south, from the city and from the country, and from different economic and social backgrounds, but who all came of age during Mussolini’s fascist regime. The interviews are conducted through the lens of food, and the women reminisce about everything from the meals they ate as children to Fascist Saturday, a weekly ritual imposed by Mussolini in which Italians were expected to participate in cultural, physical, paramilitary, and political activities.

One of Karima’s goals with the book, she says, was to counter the “deification of the Nonna” and the “surge of gastronomic nostalgia” that she says has permeated the Italian culinary landscape. She wanted to paint a more comprehensive, less romanticized picture of the endearing old ladies we see rolling out pasta dough on YouTube.

“People are emotionally invested in traditions and have strong feelings about what they believe is and isn't authentic. I try to tread respectfully but truthfully on that ground.”

Our conversation took place a few weeks before the Financial Times published an article by Italian writer Marianna Giusti titled, “Everything I, an Italian, thought I knew about food is wrong.” It’s a short profile of Alberto Grandi, author of the 2018 book Denominazione di origine inventata (Invented Designation of Origin), which maintains that many classic and traditional Italian dishes are, in fact, recent inventions. Since 2021, Grandi has co-hosted a popular podcast of the same name (I’ve mentioned it before in this newsletter). While some of what Grandi professes is not new or surprising—for example, that tiramisù was a 1980s invention—other provocative assertions have hit a nerve with (some) Italians. He claims, for example, that parmesan cheese produced in Wisconsin is more like the original cheese produced once upon a time in Parma than today’s famed Parmigiano-Reggiano. The feature in the FT, which touches on some of the same themes as Karima’s books—nostalgia, the invention of tradition—has caused a stir, so I thought I would link to it in case you’re interested. The article is paywalled but you should be able to read it here. And here’s a good perspective piece by

, which she posted after reading the FT article.Here is a condensed version of my interview with Karima, which has been edited for space and clarity.

BD: How did you become interested in the history of Italian food?

KMN: I love history and because I’m a very existential kind of person and I like thinking about or looking into the way that we inhabit this planet and needing to eat; how we transform that biological thing into something that is economic and cultural and very much emotional as well. My father was a sociologist, a professor of sociology, and so I’m very much oriented that way; my history is always social history. I’ve been interested in food and cooking since I was a small child, and when I moved to Italy that interest intensified. I’m interested in the way food reflects what people’s social class were, how certain dishes reflect the evolution of taste and appropriation, those kinds of concepts. My interest is very much about concepts and not just, “This is a recipe from bla bla bla.”

When I moved here [to Italy] I came from a place [in the U.S.] where there were just an enormous quantity of foreign food restaurants per capita. I wasn’t aware the culture shock that that would have on me—the sudden unavailability of a variety of food. I missed all those different cuisines, whether Chinese or Indian or Mexican, and so in the beginning, I spent a good deal of my time studying and cooking different cuisines. I thought that was going to be my niche in food—bringing these foreign flavors to Italy, an Italy that, at that time, was still very cautious about foreign cuisine.

At some point, the balance tipped and my focus shifted more and more to Italian food as I watched this transformation take place, this refashioning of history around Italian food. When I was young, French cuisine was the cuisine everyone aspired to; it was the measuring stick of quality and culture. Now, everything has to be Tuscan.

BD: So what accounts for this transformation?

KMN: There were a number of things that happened. There’s a long and awful history about prejudice against Italians. In the U.S., organizations like the National Italian American Foundation were established to fight Italian prejudice and to construct a sense of pride as an Italian. After World War II you had the growth of tourism and travel and, later, the rise of the agriturismo and the whole experience economy. The 1982 World Cup [which Italy won] was majorly important for Italians, to put themselves on the map that way. And then there was the Mediterranean Diet, which was—and I wrote a long thing about this—how it was developed and sort of taken over somehow by the Greeks and the Italians, even though the Mediterranean is a big place.

There’s a story about a debate that took place between two chefs, a French chef and an Italian chef, who were invited to debate their food. The French guy was going on and on about the history and the dedication of French cuisine, and so on. And then it the Italian guy’s turn and he said, well yes, that’s all fine and good and respectable but Italian food is something that people love.

BD: In Chewing the Fat you write that “Italian cookery is now considered to be one of the few classless cuisines. Rich and poor alike indulge in the same sorts of foods (albeit not of the same quality), the stereotypical table groaning with delectable offerings. But while modern legends encourage us to believe that things have been that way since time immemorial, they stand in stark contrast to documented history.” Tell us more about what you mean.

KMN: It’s difficult to imagine a time period when Italians needed encouragement to be proud of their food, but that’s the time period I write about in “Chewing the Fat.” Millions of people left Italy to escape hunger in the late 19th and early 20th century. In the countryside, many people ate polenta every day at every meal. Italian food pride was just not a thing for most people.

BD: What prompted you to write that book?

KMN: I’m a runner, and when I run I listen to podcasts. One day in 2012, I was listening to the BBC Food Programme, and something snapped. It was more people waxing poetic about grandmothers and cooking, and yet, we were never hearing the voices of these women. To me, it was perpetuating a two-dimensional vision of older women as cute and ornery, and that’s something I wanted to push back against. Because these are women who were young once, they grew up in this incredible period of Italian history. They went through this incredible experience where they were taught in every single way, every single day, that fascism is the thing—in school, in church, on Fascist Saturday. And then, suddenly, after the war, you’ve just gotta stop it, and you’re not really allowed to talk about it. It’s such an incredible sociological phenomenon of what they went through. That’s what I wanted to capture.

BD: Was it hard to get these women to open up?

KMN: There were a couple of things I did. When I recorded them, I used an iPad, which is an object they didn’t recognize as a recording device. There was always some small talk at first, and there was usually the person who brought us together, a mutual acquaintance. I also found that when I did the interviews, maybe because there was a researcher interested in her story, but that was the time when the family would sit down and listen to her, like they had never listened to her before. One of the rules of doing oral history interviews is that they should not be “contaminated” with the presence of other people. I found that, on the contrary, it was an important part of her opening up, of having that experience with the family around because, often, they had never listened to her, they had never heard her story. While she was telling her story, they were hearing it for the first time. And it just gets me. These are real women with real lives and it completely changed my life and the way I live in Italy, the way I see Italy and Italian history.

BD: In your books and articles you write about “the invention of gastronomic traditions” in Italian cuisine. But aren’t traditions an important way of preserving culinary heritage?

KMN: In The Eternal Table I talk about people in the ‘60s worrying about losing their traditions. Well, Pliny was complaining about that as well. And it’s why [Marcus] Cato even wrote De agri cultura [On Farming], because he was afraid that the Romans were losing their traditions. It’s that thing of wanting the new and keeping the old and the fear that that brings. We want so much for there to be continuity because it gives us a sense of saftety and stability. And yet, no one wants to live in a museum. Everyone wants to try new things because we’re human beings. But it also scares us. The maintenance of tradition is one thing, but it also comes at the price of food not evolving. Think about the Slow Food movement, which has done much to preserve Italian food traditions, but it’s a double-edged sword. You’re stopping food evolution in its tracks in order to save it. But at the same time, as soon as you start talking about needing to save something, then it's already gone. If there hadn’t been an evolution of food through the ages, we would not have got to that wonderful food you love.

The concepts of tradition and authenticity really blow up around [Spaghetti alla] Carbonara. The carbonara phenomenon is really outrageous, as though it had dated back to ancient Rome somehow, or 19th century coal workers. It’s a post-World War II invention and its history is full of cream and butter and other ingredients that are no longer considered authentic. It didn’t used to be precious; it’s become really precious. Now the Romans have wrapped their identity as a group around Carbonara and making it precisely right, with eggs, guanciale, and pecorino.

[You can read more on the history of carbonara here and here. Paid subscribers: On Tuesday, I’ll be sending out my heretical recipe for Double Carbonara, which will surely give some purists heart failure.]

BD: Can you describe your cookbook collection for us?

KMN: I started collecting for research, but once you get the bug for antique cookbooks, you can’t really shake it. Nothing in my collection predates the 19th century, because I can’t afford those books! Now that we are in the 21st century, I’ve started seriously collecting books from the early 20th century, also because that’s a particular point of interest for me given the fascist era. Contrary to the way I used to collect, the big names, important books, I know go for the smaller jewels. For example, cookbooks put out by banks as a New Year’s gift, or the gas company. I find those immensely fascinating. I also have a small collection of antique “La Cucina Italiana“ magazines. I have books piled up everywhere, but just the same, I wouldn’t say that my collection is large, in comparison, to other collectors I know.

BD: What’s one book in your collection that you really love?

KMN: Il Cuciniere Italiano Moderno is such a little jewel. It was originally published in 1844, mine is 1853. It has lots of early recipes for dishes we still make today, like lasagne. What interests me about this is that there are no cookbooks until after World War II that are interested in maintaining traditions. Tradition was absolutely not an interest for anyone. Modern was the word. That concept, being modern, was really important. And using the words “cuciniere Italiano” was sort of a political statement because it was before Italy became a nation.

BD: Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us, Karima.

Find out more about Karima’s work at her website, The Eternal Table.

Readers: I would love to hear your thoughts on some of the themes raised in our interview. The subject of Italian food is endlessly fascinating and debate-worthy. Please chime in by leaving a comment.

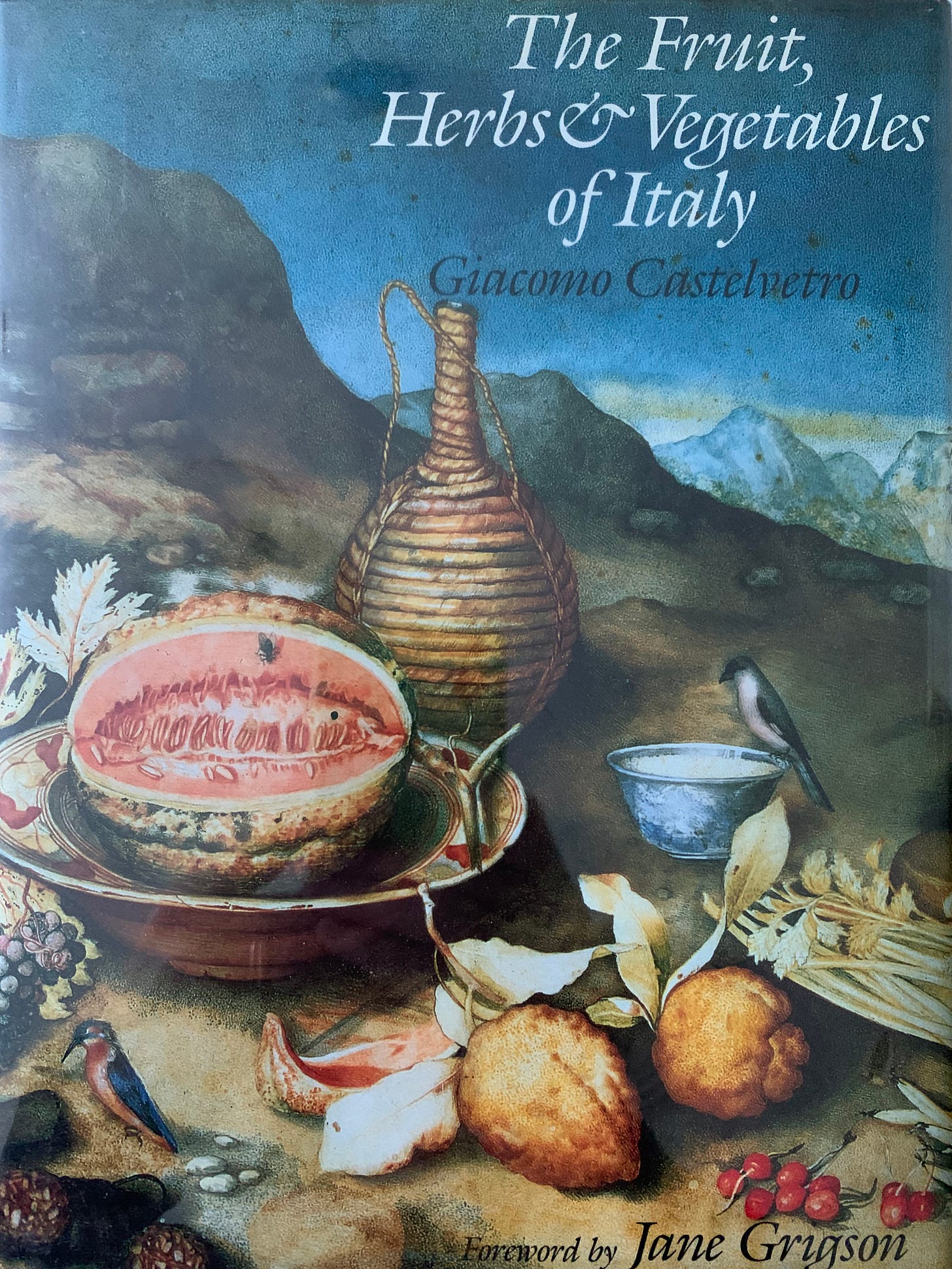

I asked Karima if she would share a recipe, and she sent one for herb-stuffed eggplant. It comes from a 17th century book called A Brief Account of all the Vegetables and all of the Fruits both Raw and Cooked that are Eaten in Italy, by Giacomo Castelvetro. (Serendipitously, I have my own copy of this book, a 1989 translation by Gillian Riley with a foreword by Jane Grigson.) Here’s what Karima wrote in an IG post about Castelvetro:

“At a time when it could cost you your life, Castevetro was a Protestant sympathizer. He escaped Italy by hiding in a basket strapped to a mule, and made it to safety in Geneva. As an educated man from a wealthy family, he entered into the graces of the aristocracy and managed to make a decent, though at times tenuous, living.

In 1580, he settled in London where he hoped to encourage an interest in Italian literature in English literary circles. During a brief return to Italy, he was held in custody by the Inquisition, but he managed to escape back to England, a fate that did not befall his younger brother, who was burned at the stake for heresy.

Castelvetro very much missed the variety of vegetables from his homeland and felt that the English would much benefit from correcting their meat, sugar, and flour-laden diet. And so, towards the end of his life, he wrote “A Brief Account of all the Vegetables and all the Fruits both Raw and Cooked that are Eaten in Italy.”

Castelvetro’s original recipe is more like a suggestion; no amounts are given, and there no specifics on which herbs to use: “One way of preparing aubergines [eggplant] is to cut them open down the middle, hollow them out and fill them with a mixture of the chopped pulp, breadcrumbs, egg, grated cheese, sweet herbs and butter or oil, and bitter orange juice. Then either grill them over charcoal, or stew them gently in an earthenware pot or tinned copper dish.”

I asked Karima about the process of adapting old recipes, and here’s what she replied: “Part of being a culinary historian is knowing a massive amount of historical recipes and being well steeped in the evolution of cooking, and so you learn to piece together, as best you can, recipes that have enormous gaps in the instructions. A culinary historian who emphasizes hands-on history, as I do, has to also be a skillful cook (as many historians are not).

“I always compare historical cookery to Early Music, no, we don’t have the same instruments, the same auditoriums, we don’t know how the composer intended the piece to sound, but that is no reason not to try to bring that music to life anyway. And if we had just thrown in the towel, think of how much poorer our cultural experience and understanding of music would be. That is what I want to do with food.”

RECIPE: Melanzane Ripiene

Herb & Cheese-Stuffed Eggplant

Even with pithy (and I don’t mean clever) supermarket eggplants, this dish was fantastic, aromatic with herbs and brightened with a spritz of fresh orange and lime juice.

I served the eggplant as a side to grilled pork chops, but it would go with many dishes: roast chicken, sausages, frittata, shrimp or swordfish skewers, grilled scamorza…you get the picture.

I realize that eggplant is not yet in season for many of us. If you don’t want to settle for supermarket eggplant, then set this recipe aside until mid-summer, but please do remember to make it!

Makes 4 servings

INGREDIENTS

4 smallish eggplants, about 900 g (2 lb) total

2 to 3 thick slices dryish bread (not fully dried), crumbed; about about 100g (3 1/2 ounces) or 2 lightly packed cups

About 5 cups mixed fresh herbs (75 g); 30 g each fresh flat-leaf parsley and basil, plus 15 g total marjoram and thyme (I added some fresh oregano to the mix since my garden is already producing it)

1 clove garlic, minced

1 cup (80g) freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Juice of 1 bitter orange or of half a sweet orange and half a large lime

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

1 egg, lightly beaten

Extra-virgin olive oil

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Preheat the oven to 350° F (180° C). Slice the eggplants in half lengthwise; you can either leave the tops on and slice through the stems or slice the stems off first. Hollow out the halves—I used a melon baller—leaving just a little flesh behind.

2. Chop the eggplant flesh finely and place it in a bowl. Add the breadcrumbs. Finely chop the herbs and mince the garlic and add them to the bread. Stir in the Parmigiano cheese and citrus juice, and season with salt. Taste and add more if needed. Fold in the egg, along with a drizzle of olive oil

3. Brush a little olive oil into the eggplant hollows and sprinkle with a tiny bit of salt. Spoon in the filling; you should have enough to fill each shell completely. Arrange them on a parchment-lined baking sheet and drizzle a little olive oil over the tops (optional). Bake, uncovered, for 30 minutes; then cover with foil and bake another 20 to 30 minutes, until the eggplant is completely tender but still holds its shape. Cool for 10 minutes and serve.

And now, a bit of housekeeping: Welcome, new subscribers. I think some of you found me through Substack’s new feature, Notes. For those of you who aren’t familiar, Notes is a new space on Substack for us to share links, short posts, quotes, photos, and more. I plan to use it for things that don’t fit in the newsletter, like work-in-progress or quick questions, comments, and engaging with readers and other writers. Here’s an example of a note I posted recently:

I hope you’ll consider joining me there. Here’s how: head to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Buona Domenica, you’ll automatically see my notes. Feel free to like, reply, or share them around.

You can also share notes of your own. I hope this becomes a space where every reader of Buona Domenica can share thoughts, ideas, and interesting quotes from the things we're reading on Substack and beyond.

As always, thank you for reading, sharing, and subscribing.

Alla prossima,

Domenica

Karima is just wonderful and this interview with two people I deeply respect made my night. I was lucky enough to see Karima not too long ago when she came to Thomas Jefferson's Monticello to do a talk (and we ate a delicious Renaissance Mac and cheese dish!) on the history of macaroni and cheese, and its journey from Rome to African American culture as it exists in America today (thanks to Thomas Jeffersons enslaved French trained chef - James Hemmings).

Here, you answered a question I that had been bugging me. I have been delving into Marcella's Essentials of Italian cooking in a cookbook club, and her recipe for carbonara was just so off (so I thought) in that it had garlic and butter (and parsley I think) and I was shocked that this would be so. Well, turns out she (being a pre war Italian) probably wasn't under the impression carbonara had such a rigid recipe - because it didn't at that point.

Thank you both for having this discussion!

Now I want to read her book on the nonne!